Beyond Disciplinarity: Genealogy of a Thought

By

Madeline Raynolds

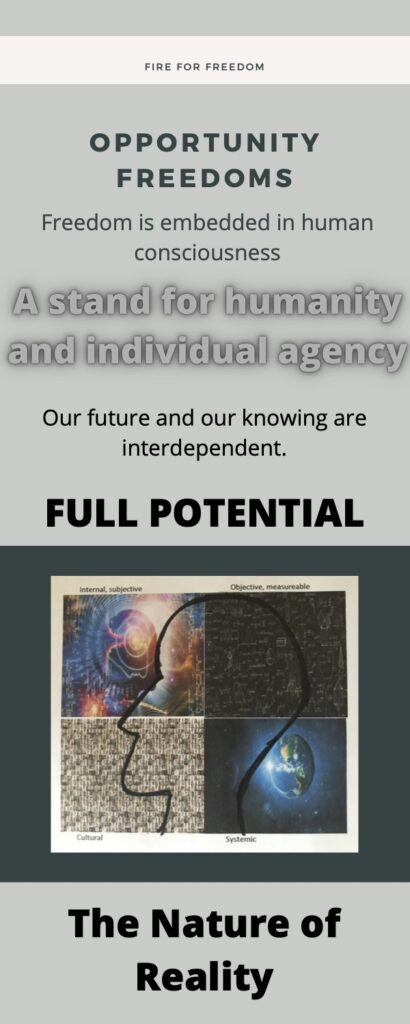

The misrepresentation of knowledge in our educational institutions has in fact led to polluting the epistemic commons contributing to the untenable power structures of the status quo. To be specific, the overemphasis of positivist approaches to knowing since the Age of Enlightenment has promoted the scientific methodological premise of “observation and evidence” (West, 1982) as the sole arbiter of Truth. Science has been the basis of our curricular models organized by the disciplines for far too long. As I wrote in an earlier essay (2020), “Foucault and others have suggested, divisions between the disciplines and the overspecialization therein distorts understanding of the nature of reality” (Foucault, 1972; Jenlink, 2005; Andersen & Grinburg, 1998). In this essay, I reflect upon my past and how I have come to believe that there are overlapping dimensions of reality that remain unidentified, unnamed and therefore misunderstood in Western knowledge. This is fundamentally important because this flawed understanding actually distorts the nature of reality and leaves individuals unable to cope with their daily lives. For these reasons, it is vital for people to see that the subjective, cultural and systemic ways of knowing must be applied alongside positivist approaches.

Let me chart the evolution of these thoughts. Like all children, I grew up heavily dependent on my parents’ views. This dependency occurs not only because parental ideas are the first to which a child is exposed, it is also an adaptive imperative to secure love and support from caregivers. Both my father and my mother were successful products of their age, members of the Great Generation who lived through World War II. Their times required this can-do resolve that focused on doing and effort. When my father was conscripted in World War II, he pulled up his socks, went off to the fields of Normandy risking his life for the common good. The actions on the home front that my mother must have witnessed were no less laborious and noble. Everyone had to do their part to combat the evil Nazi threat. They exemplified the rugged determinism that showed the way to defeat an enemy: Take action. Individualism and independence were the values they espoused and expected from my siblings and me. Their lives and success were found outside the home in the public sphere. They did honorable and necessary work in politics, education and psychology towards the cause of social justice. But they were never home. I have very few memories of either parent participating in my life except to ask what I had achieved that week. I remember wracking my brain for a list of accomplishments that I might be able to most succinctly communicate in order to get their approval. In the gap of their absence, my subjective life became extremely important to me.

Both Ivy league graduates, my parents’ education was heavily steeped in Western values and civilization building. I watched my dad give speeches in which he could move audiences with the force of his will so strongly believing that the founding of this country and the virtues of democracy were an example for all the world to see. They both accepted that the measurable world was the world that mattered and never questioned that their studies trained them to see the world this way. In the times that I tried to say something about my subjective experience, I was quickly redirected to invest in the academic program the way it was laid out. And mostly, I did. But I knew what I knew regardless of the fact that my lived experiences were almost never relevant to my studies. I wanted the assuredness that my parents had as they excelled and exalted the Western view that would set the world right one day. Whenever I called this in to question, they did not understand what was wrong with me. It was as if I were resistant or rebellious. In fact, I thought there might be something wrong with me too.

At around the age of nine, I started to have flashes of insights that I couldn’t disregard. I think, probably all children do, but we are never taught how to utilize these. Some of the thoughts I had that I kept to myself were thoughts like, I don’t think we are ever independent of each other, I think we are interconnected. And while doing isn’t bad, I wondered what is the role of being? In spite of my good grades, I always felt like an academic outsider prodding my teachers as much as I could to accept that rational scientific logic was not the only way to process the world. One such instance was in college when my paper on Locke’s An Essay on Human Understanding asserted that it was proscribing a kind of dogma that dictated the way man was meant to interact with the world like the church had. I figured, if I didn’t need the church to mediate between god and me, I didn’t need reason to mediate between the world and me. I wasn’t standing in opposition to reason, it was just incomplete. In this way, I came to recognize the voice inside my head. But given this past, I am not sure I have grown to honor this voice yet as it seems to have set me at odds. I hope one day to grow to honor this voice.

In terms of how I came to see cultural perspectives as shaping a person’s relationship with her environs, I have the first hand experiences of living in Venezuela, Mexico, Spain, France, England, Italy, China and Brazil, in that order. Over twenty years of my life have been spent outside the United States. It was refreshing to see that people in different places focused on different things. For instance, in South America, people had a colorful zest for life that I felt was missing in my puritan New England upbringing. I loved Italy for its fierce principles of family and food for which I longed. In China, the collective was more important that the individual. Out of these value systems, people organized their lives differently. These were not superficial differences of clothes, music and spices; these were completely new ways of seeing the world. One’s status in society could be totally different in two different countries which affected every aspect of life. For instance, in China, because teachers are highly revered alongside doctors, my life there as a teacher, professionally and personally, was totally different, in the classroom, in the market, in social settings and in the paycheck.

Systemic thinking became evident to me when I analyzed the historic, economic and social forces that made single motherhood so hard for my Master’s thesis at Dartmouth College. I was using my lived experience facing the challenges of single-motherhood as data in my studies to make sense of the my life’s circumstances. Was I just going crazy? What I found was that the convergence of the larger systemic trends set the conditions that made the single-mother status almost impossible. Systemic beliefs outlined by Congress in the 1996 Welfare Reform Act had as its first premise: the nuclear family is the organizing principle of society. To me that meant that my mother-only family not only had to face the economic and emotional toil that accompanies this family structure, but also had to face social stigma as well. My son’s father never had to face that. Furthermore, the 1996 bill dictated that I would have to get married if I wanted any financial wellbeing. Societal directives were affecting every part of my life. My research in to these systemic forces saved me. I wasn’t going crazy. And because these findings were so significant to me and my family’s wellbeing, I wanted to share them with others. And since I knew that single mothers don’t have time to read academic papers, I proposed to make a film to communicate with my intended audience. I learned videography and conducted qualitative research talking to other single mothers about their experiences and weaving my research throughout. Voiceless Echoes was the first film that Dartmouth accepted as a thesis for a Masters, but it was not without a lot of hoops and a delay in getting my degree.

Only now, it seems, academic institutions are starting to mention micro-phenomenology and take the subjective experience seriously. Finally we are recognizing distinctions in knowledge paradigms, philosophical assumptions and the usefulness of qualitative research. Academic papers are methodically articulating and weaving together all the fragments of thoughts I had spent a lifetime keeping to myself. The real turning point in validating my own thinking came when I read Cornel West’s “A Genealogy of Modern Racism” (1982). The line of descent this genealogy outlines is that of a mode of thought through the standardization of the discipline of Natural Science with its seemingly neutral tools to the systems of oppression that modern science has propped up. West’s lucid articulation was a profound ordering of my own thoughts. I felt like I had finally come home. Suddenly I knew for myself what liberation pedagogy (Freire, Hooks) really is. I have been gathering the evidence from different times and different disciplines from Adorno and Foucault to Bohm and Feynman and many others, finding that academia which once felt like a restrictive imposition was now providing the means through which I could set myself free, to think for myself. I want this for myself as I want this for others. That’s why we should all be working to create educational systems that provide this opportunity. It’s not the end; it’s just the beginning.

While it is true that I still don’t know how to best get people to understand the importance of seeing the subject, cultural, systemic approaches alongside science and the need to restructure K-12 learning along these lines, it’s okay. I’ll just keep chipping away. This end has been a long time coming, and while I do have some sense of urgency, I am also patient that even this will fall into place. “Do I contradict myself? Very well, then I contradict myself. (I am large, I contain multitudes.)” (Whitman, 1892) The call for interdisciplinarity is nothing less than a call to re-evaluate the conditioning perpetrated by Western knowledge on our thoughts and psyches. The Greek heroic values of individualism and domination as means to secure human’s superior sense of self-worth must come to an end. Ironically, I feel like a character in the Matrix who has had undeniable flashes of insight beyond this conditioning to see reality for what it is. I know I am not alone.

Since the origin of the species, humankind has been battling between its destructive tendencies and its generative powers. While the battle between good and evil has often been personified as an external confrontation, in fact, the source of this conflict is the war raging inside our minds. It is important that whatever theoretical research or practical initiative we propose is contextualized in this Truth (West, 2021). Not only will we have to contend with our dual essence as it reflects Nature itself, we will have to embrace the fact that this paradox is never going away. Any study or endeavor that does not hold this as the primordial condition is an incomplete effort that will have little impact to fully harness the potential of evolutionary dynamism. While humankind realistically faces its own annihilation due to global warming, ascendant authoritarianism, social and economic inequalities or a new pandemic, we are being challenged to adapt beyond the binary thinking that has separated us from the true nature of reality. In so many ways, my life and my thoughts are now meeting a critical stage. While the Western values of my conditioning have taught me that power comes from a determination to dominate over the problems and people that stand before me, I know I need, as the collective needs, another way. In the most productive and careful manner, I see the need to give up. I give up in the way Buckminster Fuller has suggested: “If you want to change how a person thinks, give up. You cannot change how another thinks. Give them a tool the use of which will gradually cause them over time to think differently.” (Senge, 2015) The perseverance will require a change of heart and practice.

References

Anderson, G. L., & Grinberg, J. (1998). Educational administration as a disciplinary practice: Appropriating Foucault’s view of power, discourse, and method. Educational Administration Quarterly, 34(3), 329-353.

Bell. L.A. 2007. Theoretical foundations for social justice. In Ma. Adams, L.A. Bell, P. Griffin (Eds). Teaching for Diversity and Social Justice (pp 1-16) New York, NY: Routledge.

Bohm, David. 1991. Thought as a System. Routledge, 3.

Foucault, Michel. 1972. The Archaeology of Knowledge. Pantheon Books, 191-193.

Freire, Paulo. 1968. Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York: Continuum.

Jenlink, P. M. 2005. Editorial: On bricolage and the intellectual work of the scholar-practitioner. Scholar-practitioner Quarterly, 3(1), 3.

Raynolds, M. 2020. Action Research #2. Northeastern University

Senge, P., Hamilton, H., Kania, J. 2015. The Dawn of System Leadership (SSIR). Stanford Social Innovation Review: Informing and Inspiring Leaders of Social Change. Retrieved December 10, 2021, from http://ssir.org/articles/entry/the_dawn_of_system_leadership.

West, Cornel. 1982. A Genealogy of Modern Racism, Prophesy Deliverance! An Afro-American Revolutionary Christianity, Westminster Press.

West, Cornel. 2021. The 2021 Holberg debate: “Identity politics and culture wars”. Holbergprisen. Retrieved December 13, 2021, from https://holbergprisen.no/en/2021-holberg-debate-identity-politics-and-culture-wars.

Whitman, W., Nash, J., & Whitman, W. (1924). From Whitman’s Song of myself. London: Poetry Bookshop

Wilber, Ken. 1995. Sex, Ecology, Spirituality. Shambhala Publications Inc.

Madeline Raynolds is a freelance thinker who conferred degrees from New York University (BFA), Dartmouth College (MALS) and Middlebury College (MA) and has worked as an international educator for the last 30 years. Her work in schools include being a teacher, curricula developer, and school administrator in the United States as well as in Italy, Portugal, China and Brazil. Madeline is presently working on a Doctorate in Education and the principles of sustainability in all aspects of her life in Woodstock, Vermont.